Canada wants to give itself the means to regain influence on the international stage by changing the way it conducts diplomacy in the world. To do this, the Secretary of State, Mélanie Joly, presented to a task force meeting in Ottawa last week a working document that is the result of an internal review of the functioning of Canada’s three components of Global Affairs: Department of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and International Development.

After a year of consultation and reflection, officials have produced a high-quality document whose recommendations will be implemented over the next three years. These recommendations revolve around four areas of action: acquiring new policy expertise; increase the country’s presence abroad; investing in people; and finally, enhancing the tools, processes and culture needed to carry out Canada’s diplomatic mandate. Readers will understand that this document is not a foreign policy statement, but a guide to its implementation.

Over the last few years, I have frequently highlighted in these pages and elsewhere how Canadian diplomacy has become a business run by effective leaders rather than a box in which diplomats generate ideas for improving international relations. Both actions are necessary for active diplomacy, but the first clearly takes precedence over the second. The document apologizes for the situation: “We read certain employees specifically [ceux] with deep expertise in certain areas and territories, feel increasingly disadvantaged over time, including in promotion processes, where the focus is on leadership skills rather than expertise […]. »

The results of this leadership push were not long in coming. The last time Canada made its mark on the international stage was in 1996-2000 thanks to a spectacular diplomatic initiative by Lloyd Axworthy, one of our great foreign ministers, and a group of brilliant diplomats.

The government wants to improve this situation by investing in better internal training, by prioritizing the most creative, by encouraging a spirit of initiative and risk, by recruiting more specialists and by offering better personal and professionalism. But reversing a trend that has favored twenty years will take time and constant monitoring. Department officials must ensure that thinkers rise to the top as quickly as leaders do if they are to create a critical mass of advisers capable of explaining to their masters of politics the best options for Canadian diplomacy.

“Diplomacy is about influence,” the document says, and much of that influence is exercised through presence on the ground. In this area, the findings set out in the working documents are overwhelming for the G7 countries. We are clearly not living up to our claim to play a role on the international stage. Canada has 178 missions (embassies and consulates) in 110 countries, of which 40 are concentrated in 4 countries: the United States, China, India and Mexico. This mechanism has been stable for twenty years, while the competition between the big and middle powers for influence in international affairs has never been more intense. Thus, South Korea is present in 191 countries, Germany in 153 countries, Turkey in 136 countries, and tiny Norway, with its four million inhabitants, in 81 countries.

The situation is no better in international organizations. The number of staff in Canada’s representation to the UN is now one of the lowest among G7 partners and competitors, with 25 staff compared to 60 to 150 staff for the other six G7 members: Germany, Italy, the United States, France, Japan and the United Kingdom. The working document contains several recommendations for increasing Canada’s presence, but does not set any targets aimed at approaching the systems used by our allies. The lack of human resources could have a direct impact on Canada’s ability to campaign well for seats in major international forums, such as the Security Council.

Initiatives to change Canadian diplomatic practices are the first step in restoring the country’s credentials. However, it cannot be satisfied to be an administrative exercise meant to tighten bolts, repaint walls or hook up our diplomats with the latest and most modern technology. It must be accompanied by an idea of the importance to give to Canadian action on the international stage. Last year’s Indo-Pacific Strategy publication went in this direction for this region of the world. There is still much to be done for other areas.

To see in the video

“Aficionado Twitter ninja. Infuriatingly humble problem solver. Gets dropped a lot. Web geek. Bacon aficionado.”

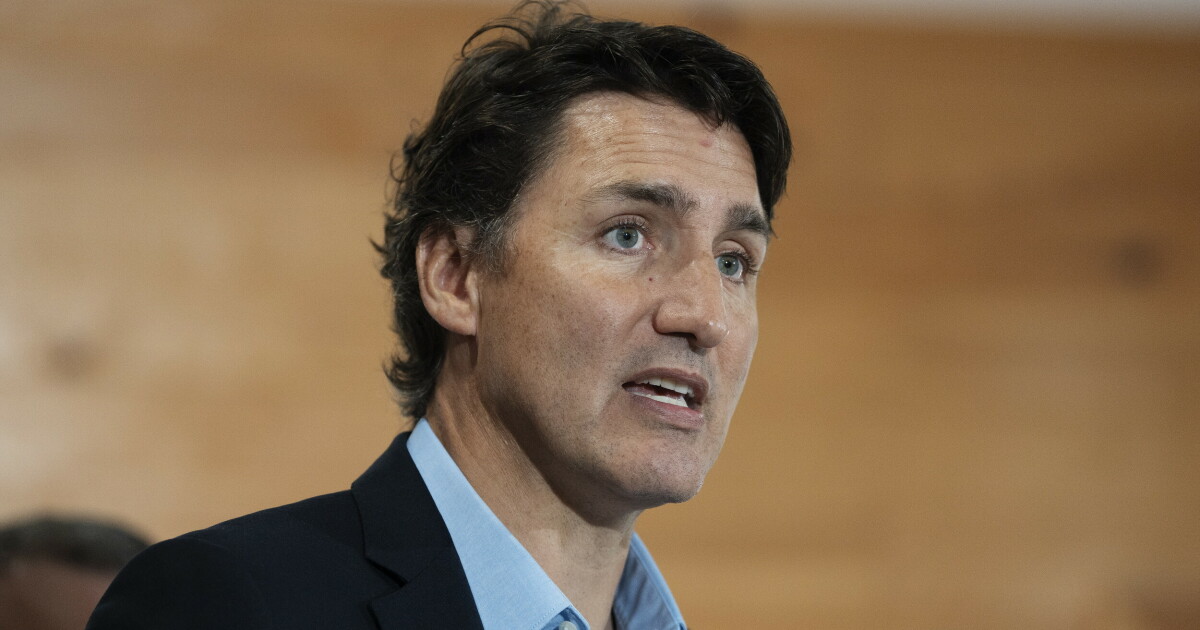

![[Opinion] The difficult task of changing the practice of Canadian diplomacy](https://media1.ledevoir.com/images_galerie/nwd_1502528_1159471/image.jpg?ts=1686556944)